Fotografiranje trkov kapljic je ena najbolj fascinantnih zvrsti makro in visokohitrostne fotografije, kjer se srečata fizika tekočin in estetska umetnost.

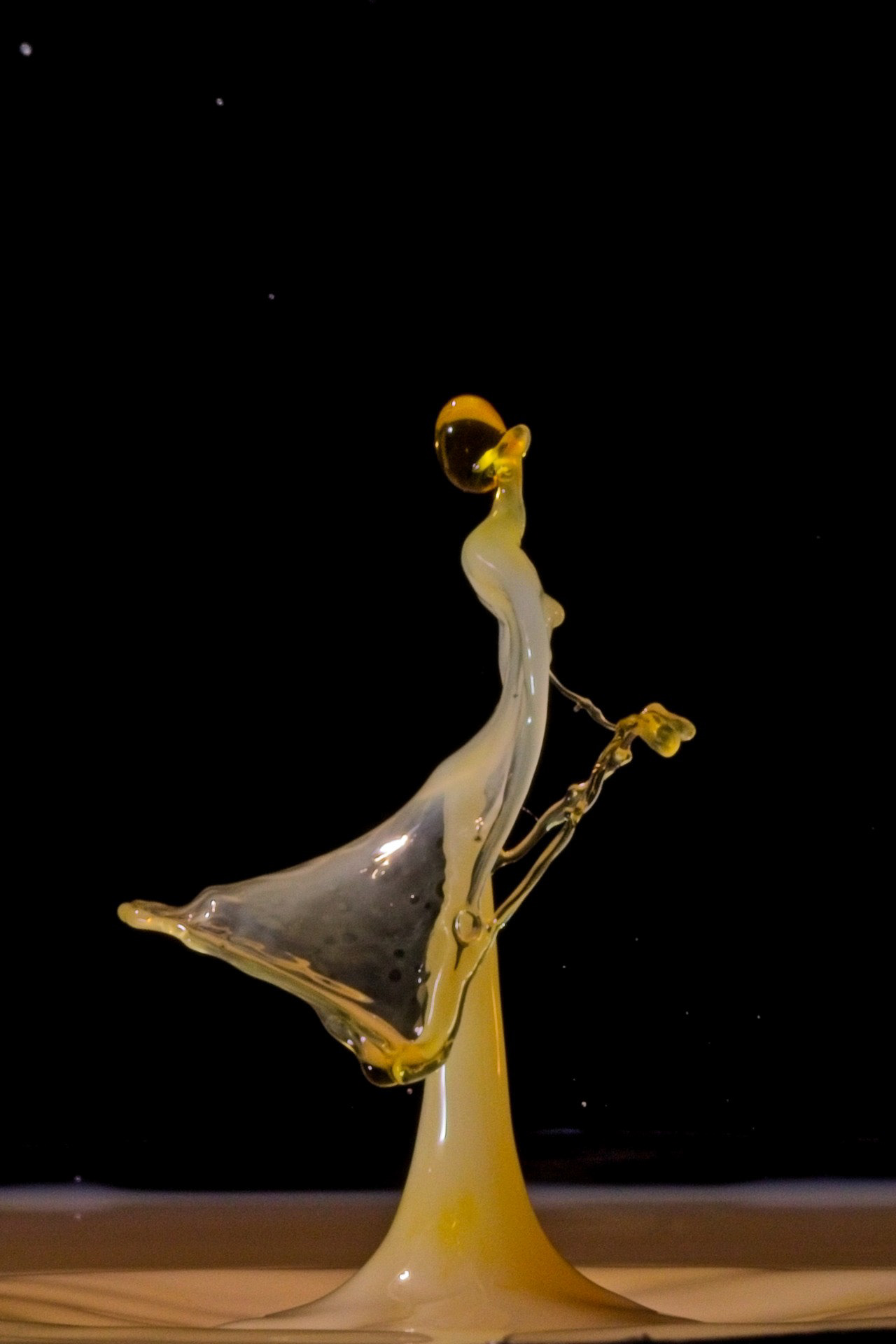

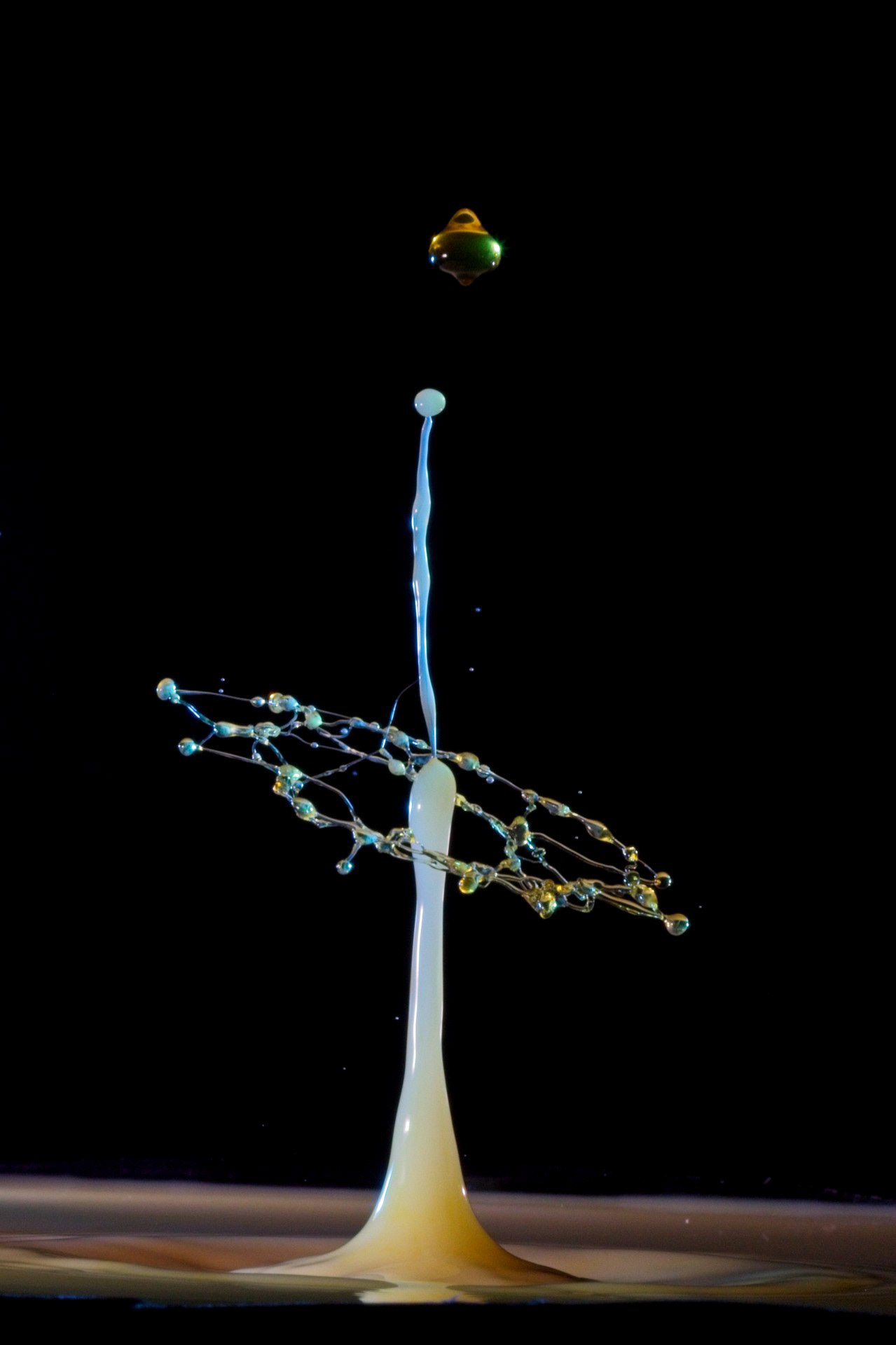

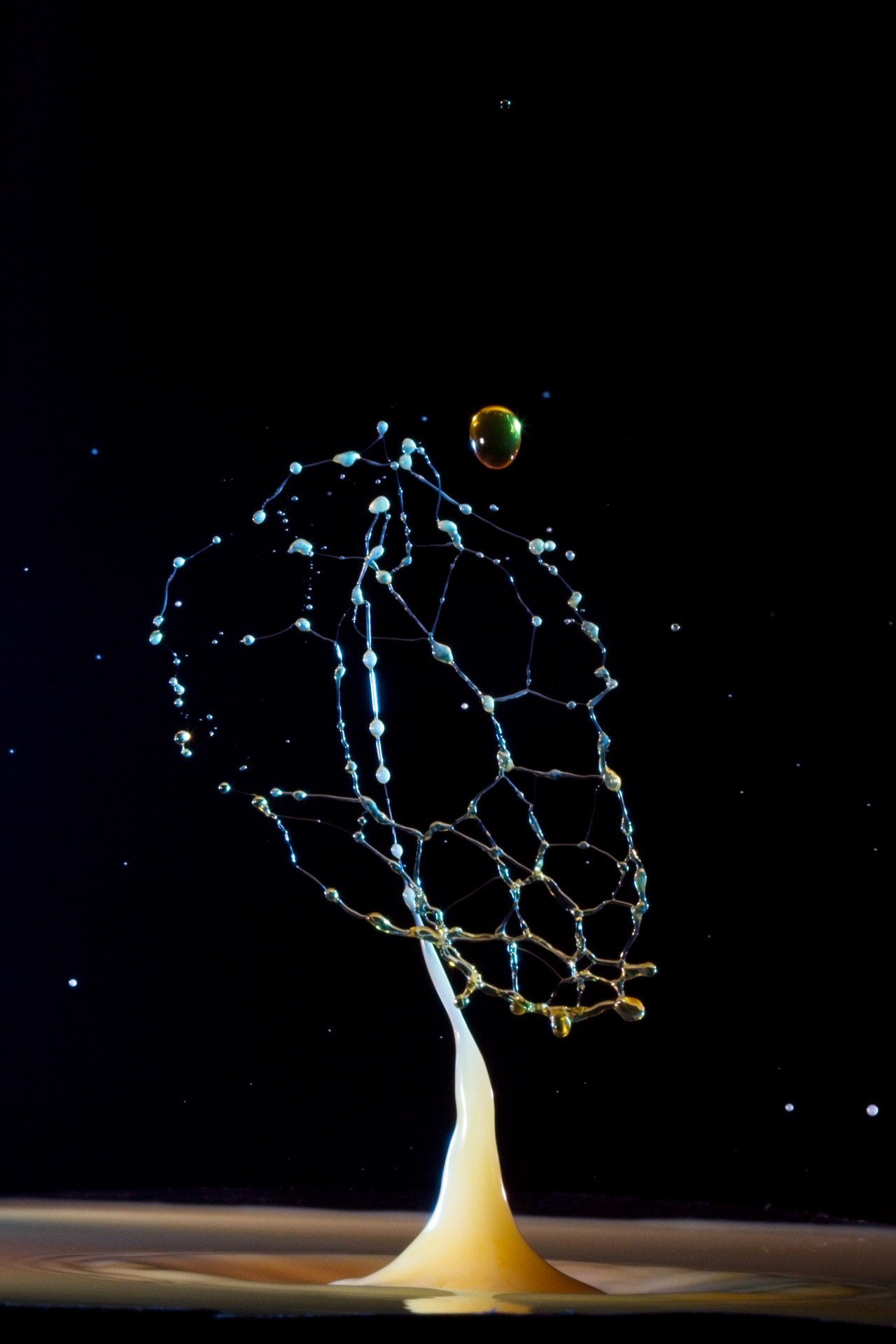

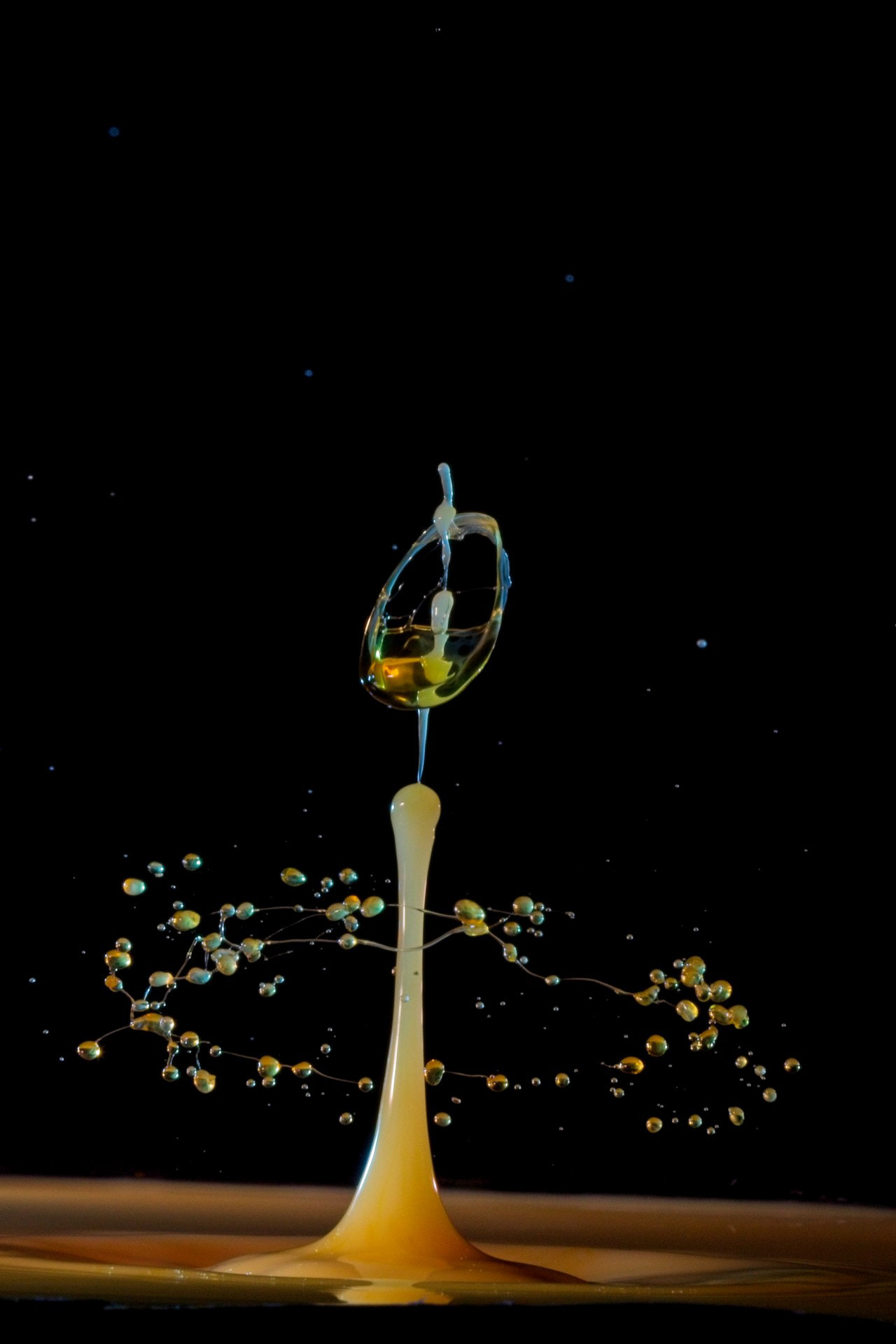

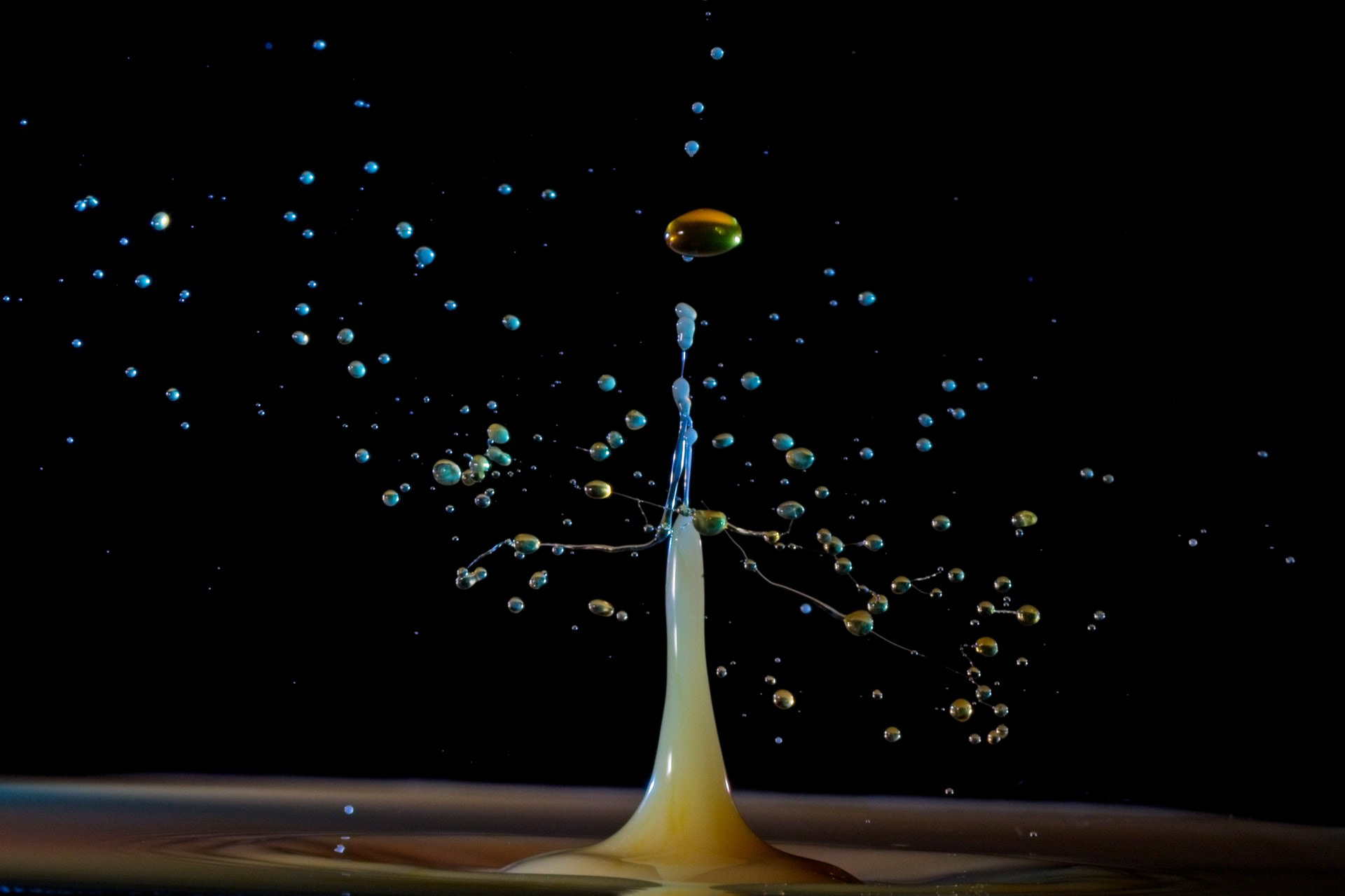

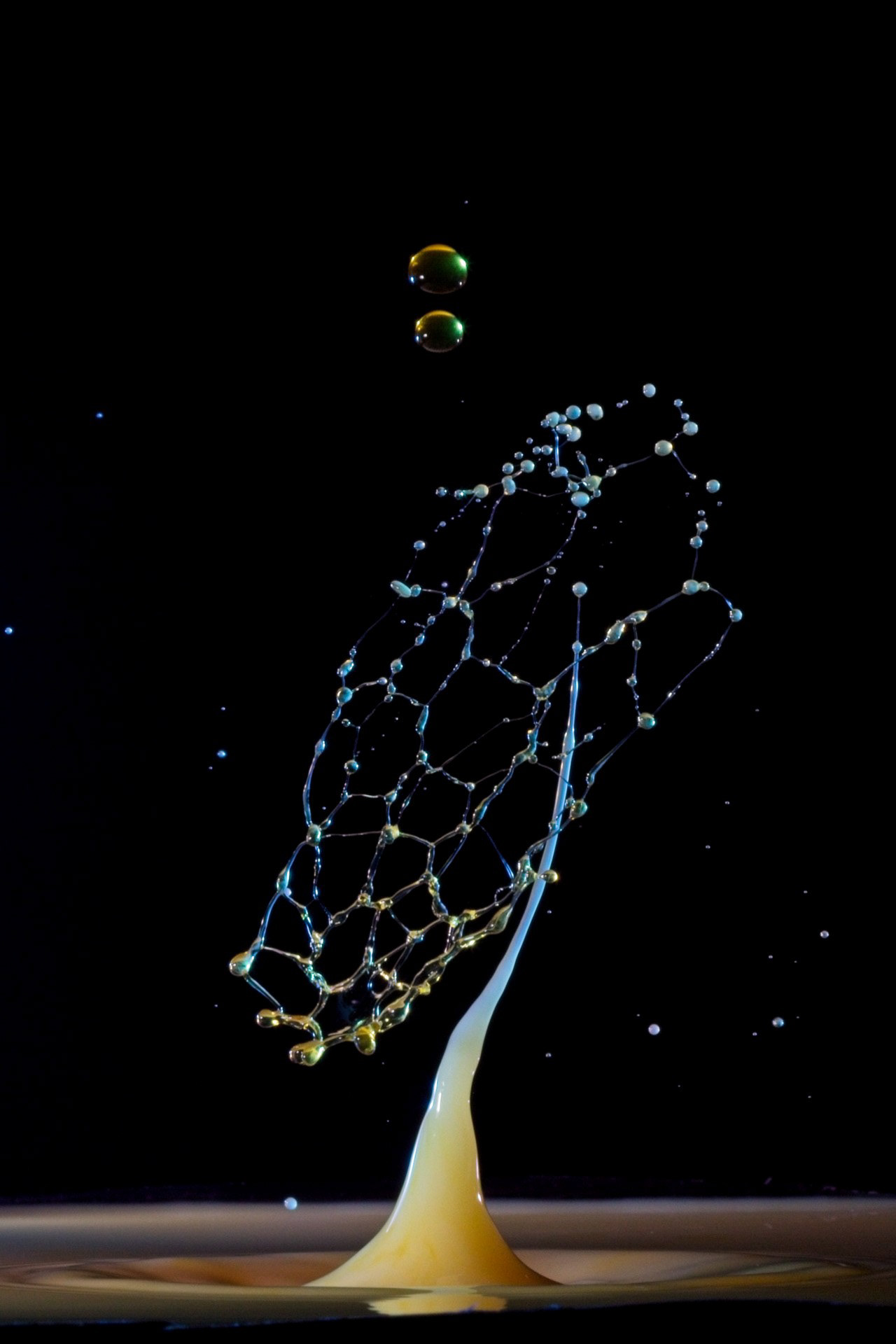

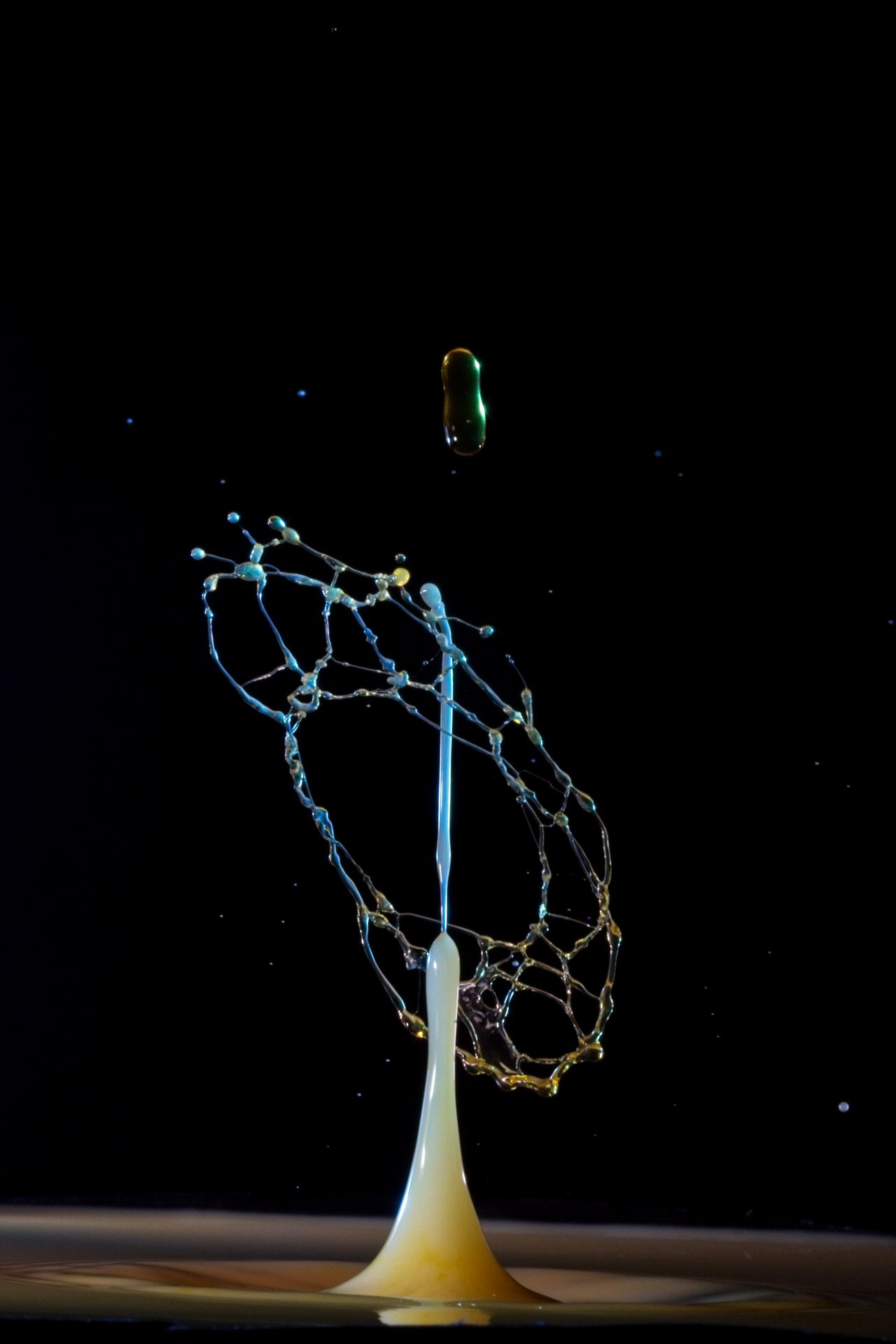

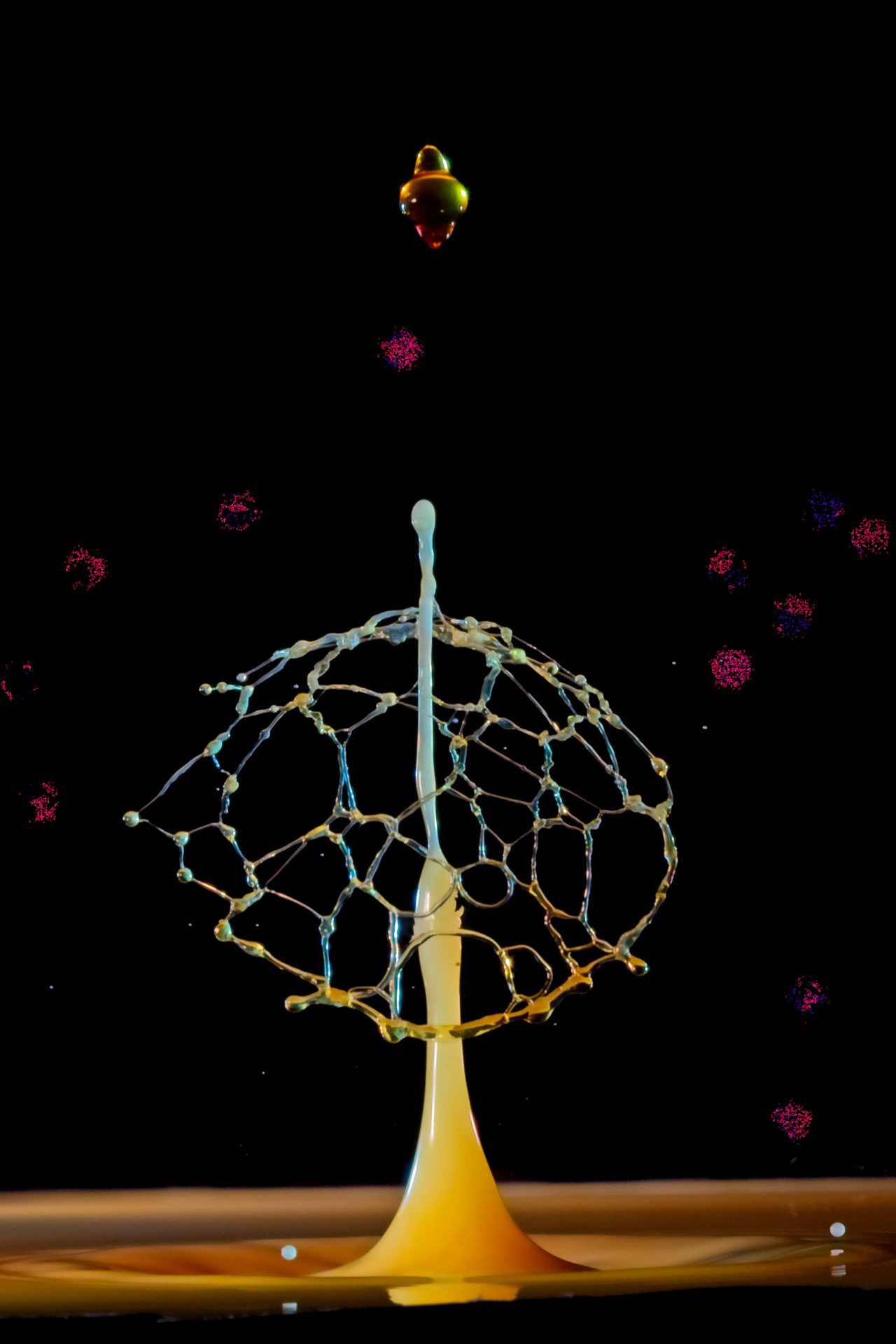

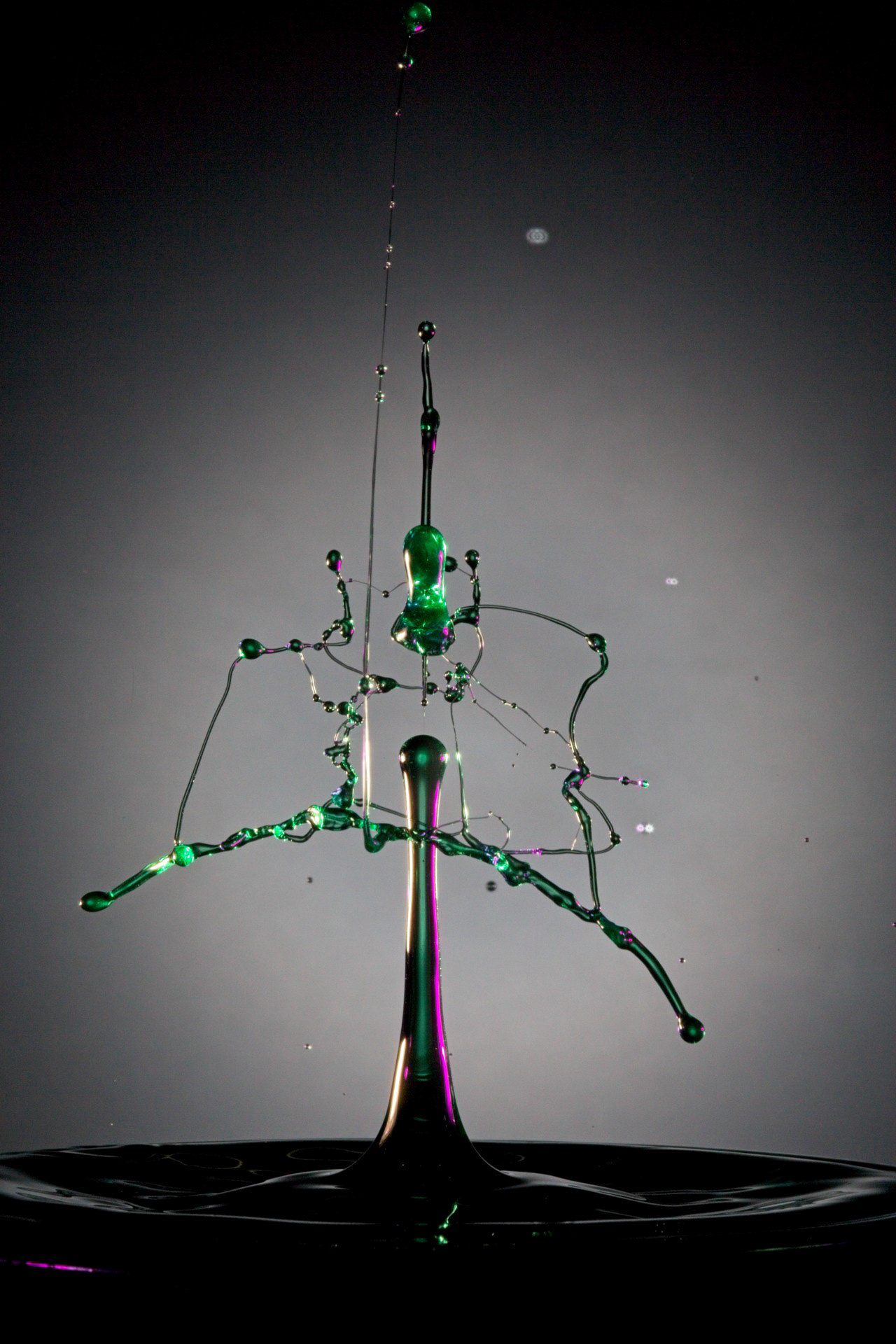

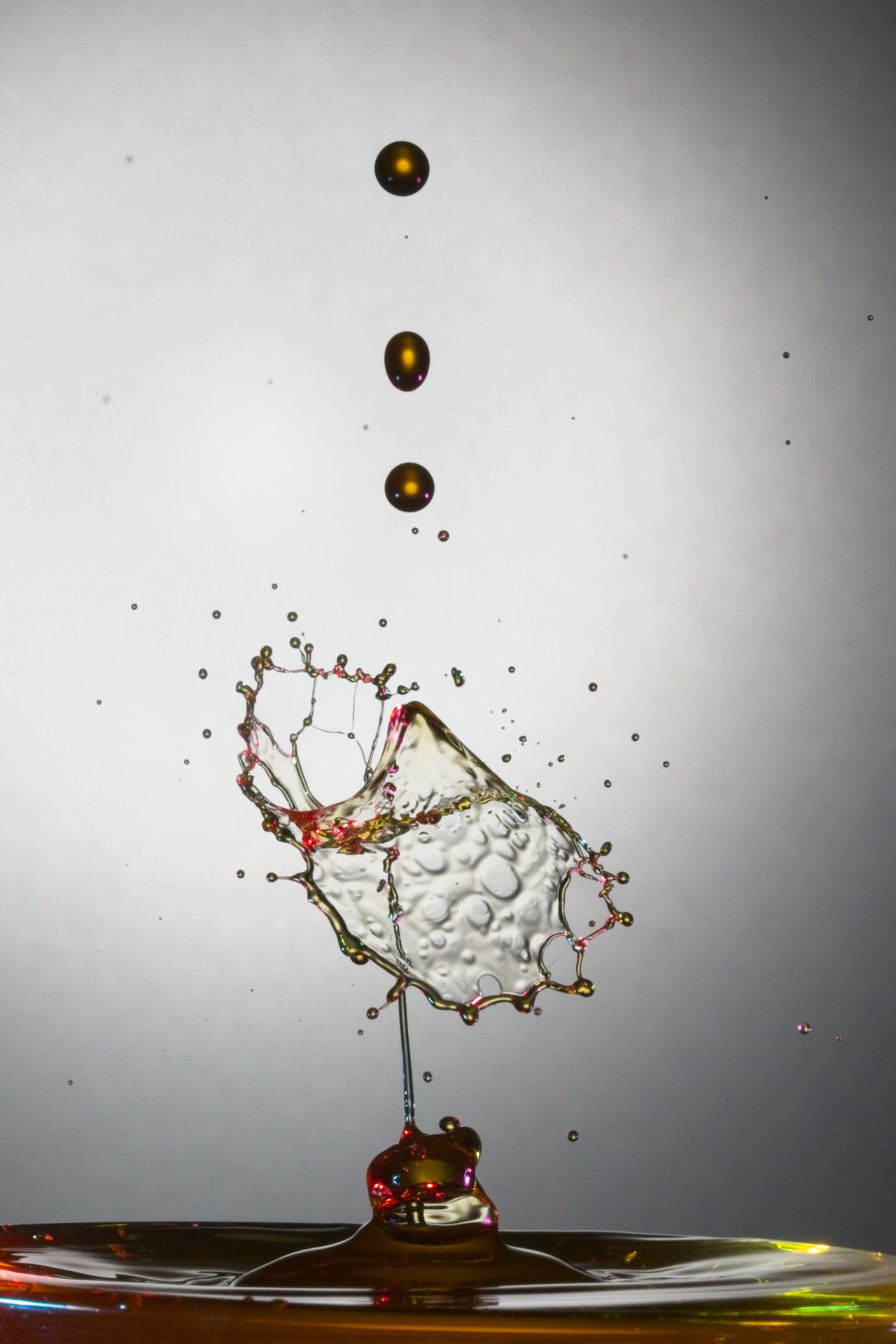

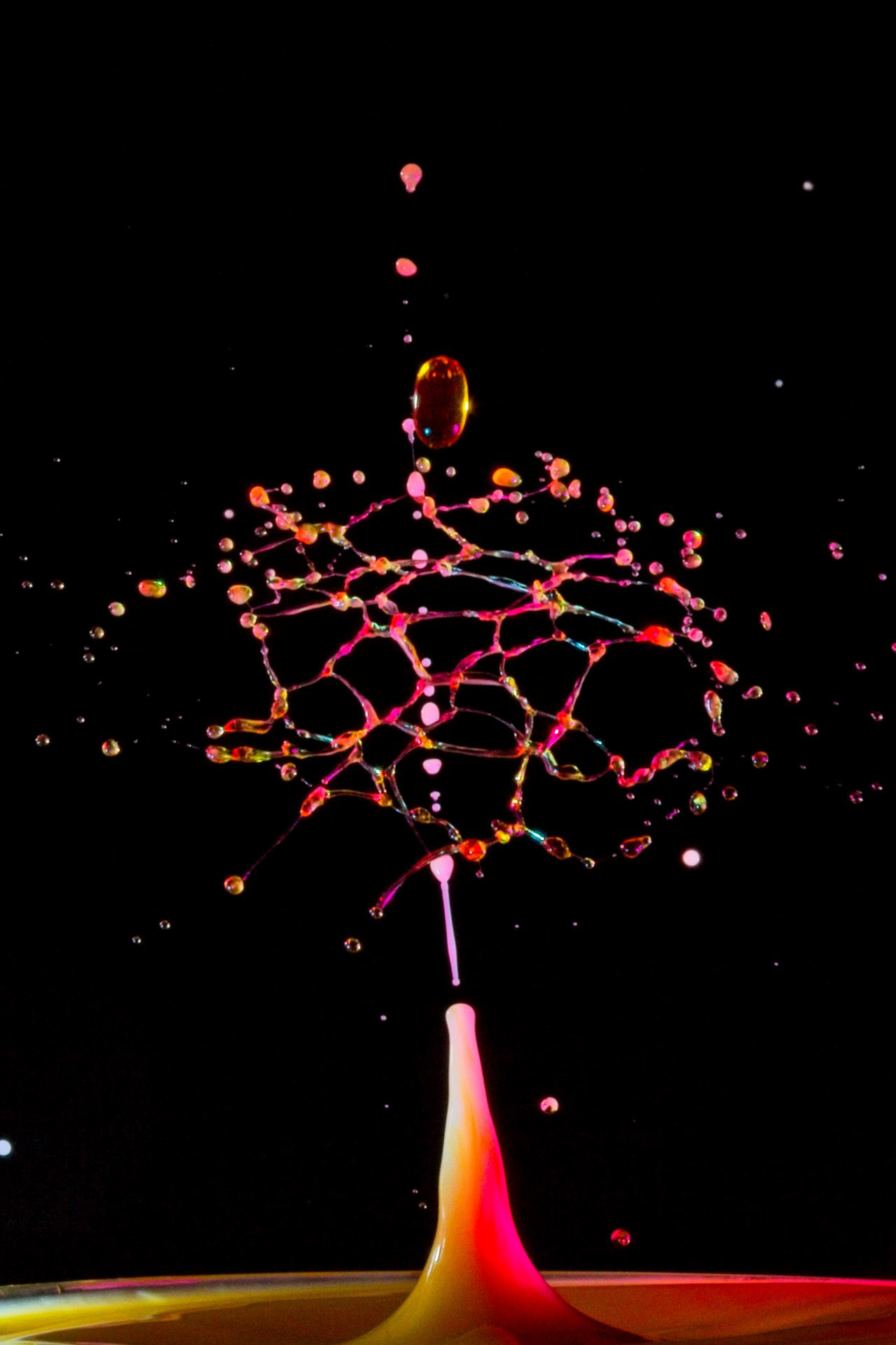

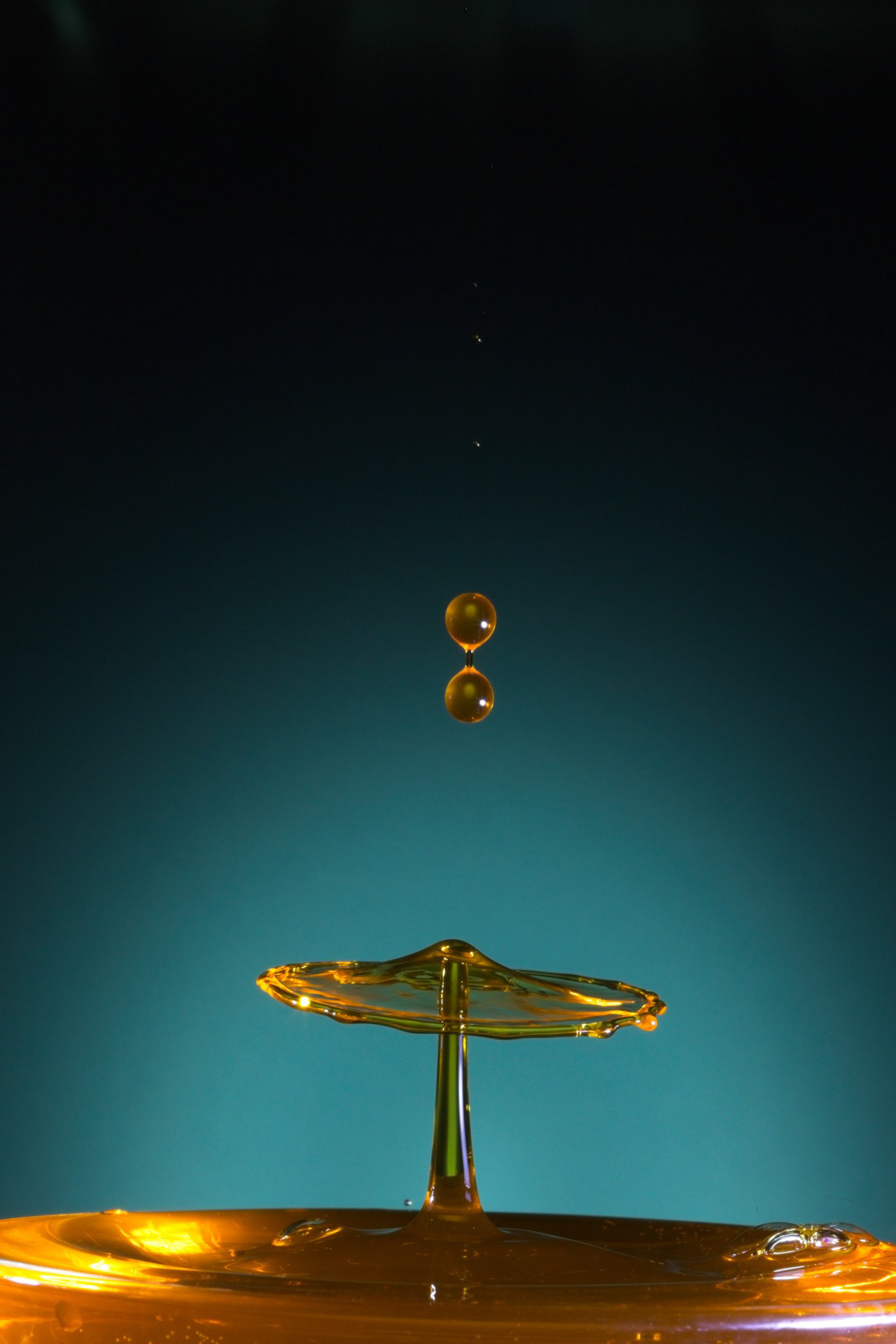

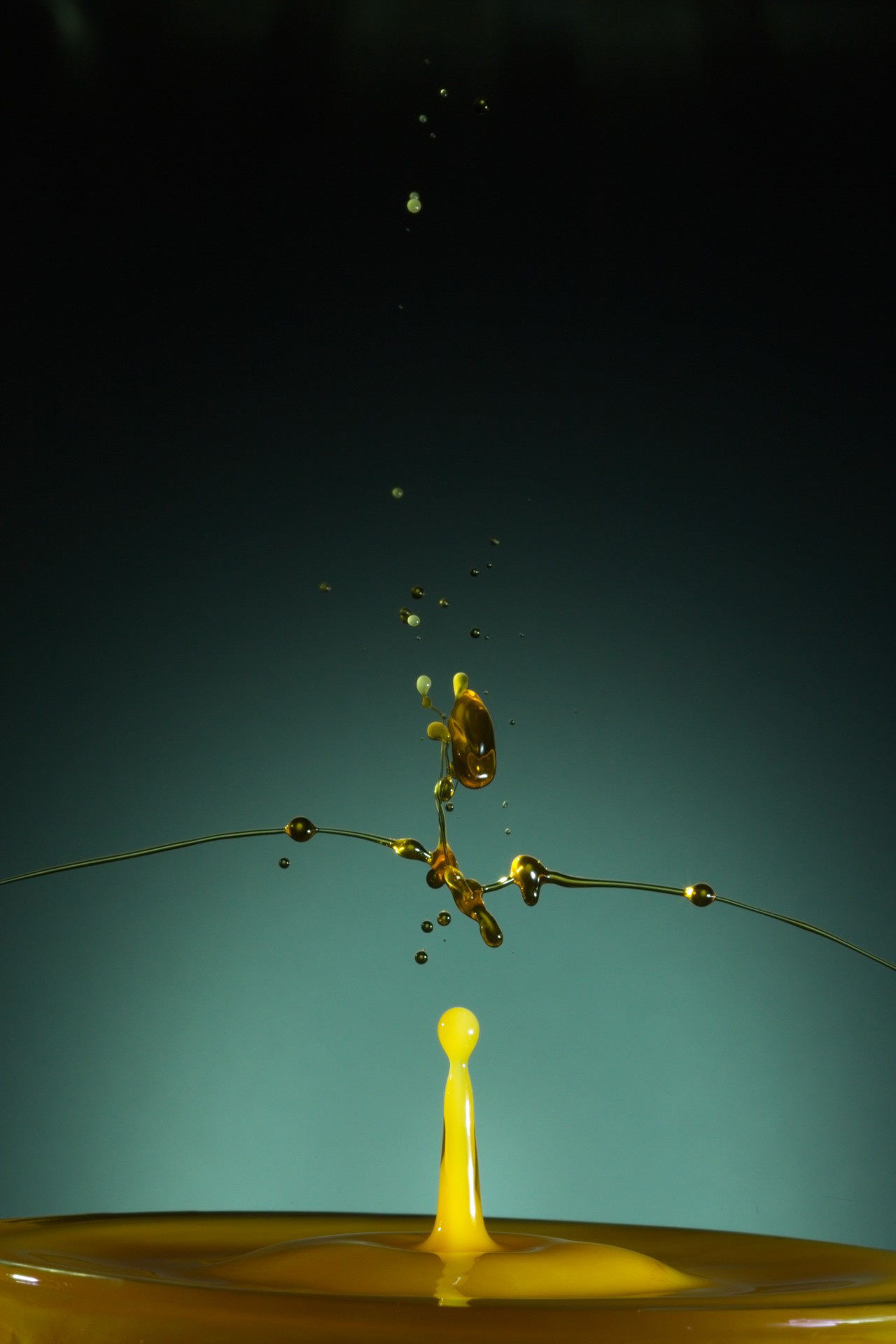

Gre za zajem trenutkov, ki so človeškemu očesu nevidni – ko kapljica tekočine zadene površino ali drugo kapljico in za delček milisekunde ustvari krone, stebričke, dežničke, gobice ali celo oblike, podobne cvetovom. Vsaka fotografija je unikatna, saj že minimalna sprememba časa, višine padca ali viskoznosti tekočine popolnoma spremeni rezultat.

Ključ do uspeha ni hiter zaklop fotoaparata, temveč zelo kratek blisk (pogosto 1/20.000 s ali še krajši), ki dejansko »zamrzne« gibanje. Zato se kapljice običajno fotografira v temnem prostoru, pri čemer se blisk sproži pomočjo časovnikov in mikrokrmilnikov. Fotograf postane nekakšen dirigent, ki usklajuje čas padca, zamik bliska in barvo ozadja.

Posebno poglavje predstavlja eksperimentiranje s tekočinami. Vodi se pogosto dodaja glicerin, mleko ali barvila, da kapljice postanejo bolj oblikovno stabilne in vizualno izrazite. Prav tu se znanost prevesi v ustvarjalnost – fotograf ne dokumentira več le fizikalnega pojava, temveč ustvarja abstraktne skulpture iz tekočine.

Fotografiranje trkov kapljic zahteva potrpežljivost, natančnost in veliko poskusov, a nagrada je izjemna: trenutek popolne simetrije in lepote, ki obstaja le nekaj tisočink sekunde – in ostane ujet v fotografiji.

Drop collision photography is one of the most fascinating areas of macro and high-speed photography, where the physics of liquids meets visual art.

It focuses on capturing moments that are invisible to the human eye—when a falling drop strikes a surface or collides with another drop and, for a fraction of a millisecond, creates crowns, columns, umbrellas, mushrooms, or flower-like shapes. Every image is unique, because even the smallest change in timing, drop height, or liquid viscosity produces a completely different result.

The key to success is not a fast camera shutter, but an extremely short flash duration (often 1/20,000 s or shorter), which actually freezes the motion. For this reason, drop collisions are usually photographed in a dark environment, with the flash triggered precisely by the falling drop—using timers, sensors, or microcontrollers. The photographer becomes a kind of conductor, synchronizing drop timing, flash delay, and background color.

Experimenting with liquids is an essential part of the process. Water is often mixed with glycerin, milk, or dyes to improve shape stability and visual impact. This is where science turns into creativity: the photographer no longer merely documents a physical phenomenon, but creates abstract liquid sculptures.

Drop collision photography demands patience, precision, and many failed attempts, but the reward is exceptional—a moment of perfect symmetry and beauty that exists for only a few thousandths of a second, preserved forever in a photograph.